With Todd Gurley and Jameis Winston investigations underway, much attention is being (re)directed to the NCAA’s amateurism claims.

Setting the tone for the current debate is Judge Claudia Wilken’s recent ruling in the O’Bannon case against the NCAA, where she found the NCAA in violation of antitrust law by preventing football and men’s basketball players from being paid for use of their names, images and likenesses.

Who are you calling an amateur?

In a culture where the tables have turned and more and more children proclaim their goals of being basketball and football players instead of doctors and fire fighters when they grow up, I don’t believe there’s anyone so naïve to think that being a student is the top priority of a student-athlete. In fact, the whole system would emphasize just the opposite. Down to the high school level (and even before then, I’d be willing to bet) coaches, teachers and administrators often collude to create the most advantageous circumstances to further the advancement of their athletes. Whether this means inflating grades or granting unheard of extensions for assignments, overlooking necessary disciplinary action or softening sanctions, athletes receive special treatment in order to remain eligible to remain in the game. I’ve even known parents to transfer their students from private to public school or across school districts if it meant more playing time and more exposure for their athlete.

This pattern of behavior makes clear early on the prioritization of athletics over academics, a pattern only to be exacerbated at the collegiate level where rigorous travel and training take precedence over class schedules, and athletes may or may not be steered toward particular classes and professors to help them maintain academic eligibility. Athletic opportunities govern families’ choices about when, where and for how long young athletes pursue an education, because these days, collegiate athletic programs function more like a D-League than anything else. And let’s not overlook the fact that near quarter of a million-dollar educations suddenly have zero dollars attached for the student who shows promise on the athletic field. That’s not generosity, that’s business. Especially when guys like Todd Gurley are easily raking in several times more than their share of tuition dollars.

Back to business.

Let’s be real. The athletes driving these DI and DII revenue sports are only considered “amateurs” because they are not allowed to share in the profits they generate, not because they’re only in it for the love of the game. We’ve seen this to be the case with the countless athletes past and present (and some unknown I’m sure) who have gotten themselves and their schools in trouble for accepting money from alumni or agents for one reason or another. At the end of the day, these athletes work extremely hard to prove themselves from the very beginning of their little league careers for a shot in the pros. That’s the point—to get to the big money—and for good reason. The story of the athlete who comes from a socioeconomically disadvantaged background and has dreams of “making it” and supporting his or her family is not uncommon. But the turning point shouldn’t necessarily be years down the road on draft day if the players are actually generating revenue before then… just without the ability to realize those gains.

Train up a child…

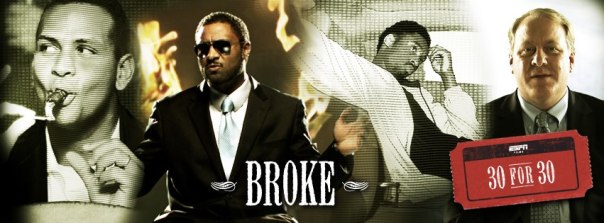

If a young athlete’s whole life is dedicated to training and improvement on the playing field, shouldn’t they also be instructed how to manage the success they’re working toward along the way? We hear it all the time: “Multi-million dollar athlete goes broke.” They even made a movie about it. But why? Because they clearly lacked fiscal prudence. Next question: How can they know if they’re never taught?

There can be no expectation of responsibility when a 19 or 20-something year old, fresh out of a year or two of college, is handed tens of millions of dollars with no guidance as to what to do with it, especially when the lifestyles of everyone else in the locker room suggest big houses, fast cars and flashy wardrobes are the only way to say “I made it.” (Though those may be the least of their vices…)

The point is this: If we teach our athletes how to manage their money (and otherwise function like responsible adults) early on, they’ll have a much better chance at success later in life, whether as a professional athlete or corporate professional. In fact, the O’Bannon ruling creates an opportunity to do just that.

Judge Wilken’s injunction made it permissible for schools to pay their athletes more than $5,000 per year in exchange for the use of their names, images and likenesses for revenue-generating endeavors. That’s at least $20,000 to manage. How will they do it?

To further support their student-athletes, universities can follow the lead of schools like the University of Illinois that facilitate a life skills program designed to develop the student-athlete as a whole. Programs like these can include financial education components that will help students learn essential principles for spending and investing their money wisely now and in the future. What’s great is that in its Statement of Policy regarding agents and advisors, Illinois has prohibited communications between agents and financial advisors and student-athletes, unless authorized by the university’s life skills coordinator. This supports an environment in which athletes can learn about agency/representation, financial management, etc. and be shielded from some of the risk of exploitation or misguidance (notwithstanding any deliberate action from either side).

The future of the amateur athlete is uncertain, at least as far as the NCAA regulation is concerned. With the O’Bannon ruling, it seems that collegiate athletes are ever so slowly gaining momentum toward reclaiming economic ownership of their personal brands, but further developments are unpredictable and certainly remain to be seen.